India needs to deploy public capital strategically to bridge the financing gap for green steel projects, which are technically proven but still considered risky for private finance — and to avoid carbon lock-in from its planned capacity expansion, according to a new briefing note by the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA).

The analysis highlights that with 92% of India’s planned steel capacity expansion from 180 million tonnes (Mt) to 300Mt not yet built, technology choices made now will influence emissions for 30–40 years. Steel plants typically operate for decades once constructed, making early public finance intervention important.

“Carbon lock-in occurs when steel plants with 30–40-year lifespans are built with conventional technology, locking in emissions until 2060–70. This could affect India’s net-zero goals,” notes Saurabh Trivedi, Sustainable Finance Specialist, IEEFA, and a co-author of the note.

Beyond climate implications, traditional blast furnaces use metallurgical coal as a primary energy source, largely imported from Australia. As India adds more BF-BOF capacity, the country’s met coal imports are expected to nearly double by 2035, posing an energy security challenge.

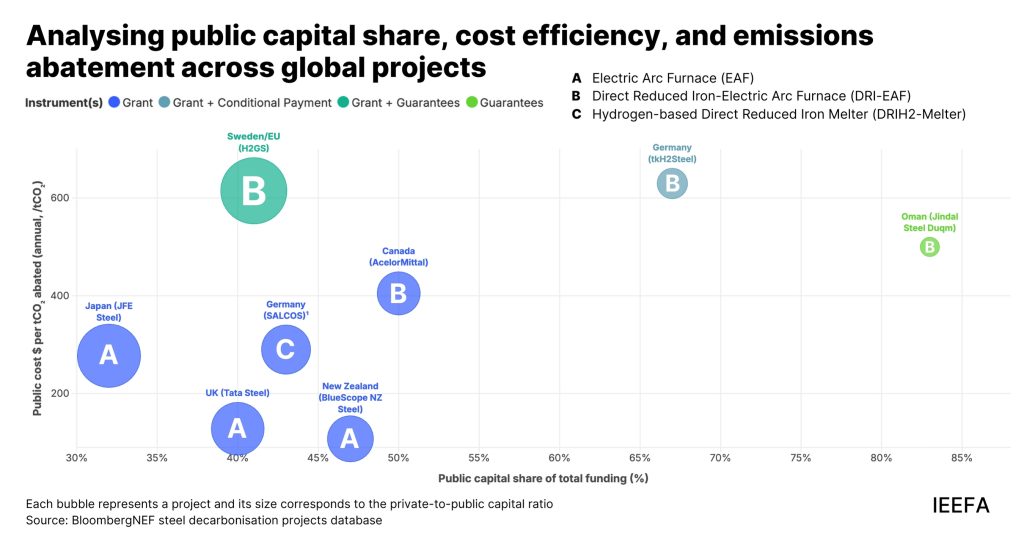

IEEFA’s assessment of select international green steel projects shows that while public support is needed to make these technologies commercially viable, the efficiency of public spending varies from US$110 to US$1,168 per tonne of CO₂ abated, depending on whether projects use Electric Arc Furnace with scrap or Direct Reduced Iron–Electric Arc Furnace, and on the level of public support provided. Credit guarantees achieve 2.4:1 private capital mobilisation compared to 0.5-1.5:1 for direct grants.

“While venture capital and private equity typically fund emerging technologies, these sources may not be well-suited for green steel given its low technology readiness level, massive capital requirements, and extended payback periods,” says Meenakshi Viswanathan, Energy Finance Intern at IEEFA and a co-author of the note.

Nearly US$24 billion has been injected into steel decarbonisation projects. Virtually every major green steel initiative globally has relied on substantial public finance to reach viability.

The Indian government is also formulating a National Mission for Sustainable Steel with an estimated Rs5,000 crore (US$600 million) outlay aimed at decarbonising steel production. The programme is likely to offer production-linked incentives, concessional loans, or risk guarantees to steelmakers, with up to 80% of funds expected to support secondary steel mills.

Another key pillar under development is Green Public Procurement (GPP). A draft GPP policy would mandate that 25–37% of steel used in public projects be low-carbon, creating an assured domestic market for green steel. However, implementing GPP has been challenging — a proposal to establish a centralised agency for bulk procurement of green steel was rejected by the Ministry of Finance in 2024.

Under the Carbon Credit Trading Scheme, set to begin trading in October 2026, emissions intensity targets will be imposed across nine industrial sectors, including steel. While this could reward cleaner steel production, its impact will depend on carbon pricing levels which will be driven by target stringency.

“These measures signal government intent, but the scale of proposed funding remains modest,” says Viswanathan.

Steelmakers are tapping into capital markets through Sustainability-Linked Bonds and green bonds. “However, these instruments support incremental improvements rather than the deeper technological shifts required for complete decarbonisation,” notes Trivedi.

The analysis reveals how markets differentiate between green steel types. Gas-based Direct Reduced Iron projects like Cleveland-Cliffs in the US and ArcelorMittal in Germany failed to secure buyer premiums and were cancelled despite grants, while integrated hydrogen-based projects like Sweden’s Stegra secured long-term offtakes with 20–30% premiums.

“The market data shows buyers will pay premiums for steel with end-to-end green credentials spanning renewable energy, hydrogen production, and steelmaking,” says Viswanathan.

Based on these insights, the briefing note proposes three targeted instruments for India: a credit guarantee facility through government-backed institutions, creating contingent rather than direct budget liabilities; competitive product-based Contracts for Difference using reverse auctions to discover true green premiums; and dedicated project preparation facilities for MSMEs.

“India’s approach will differ from the West — focusing on maximising impact through instrument design rather than large direct subsidies,” concludes Trivedi. “Ultimately, India’s green steel transition demands strategic public capital deployment that ensures judicious use of taxpayers’ money, while spurring innovation and investment from industry, global financiers, and technology providers.”